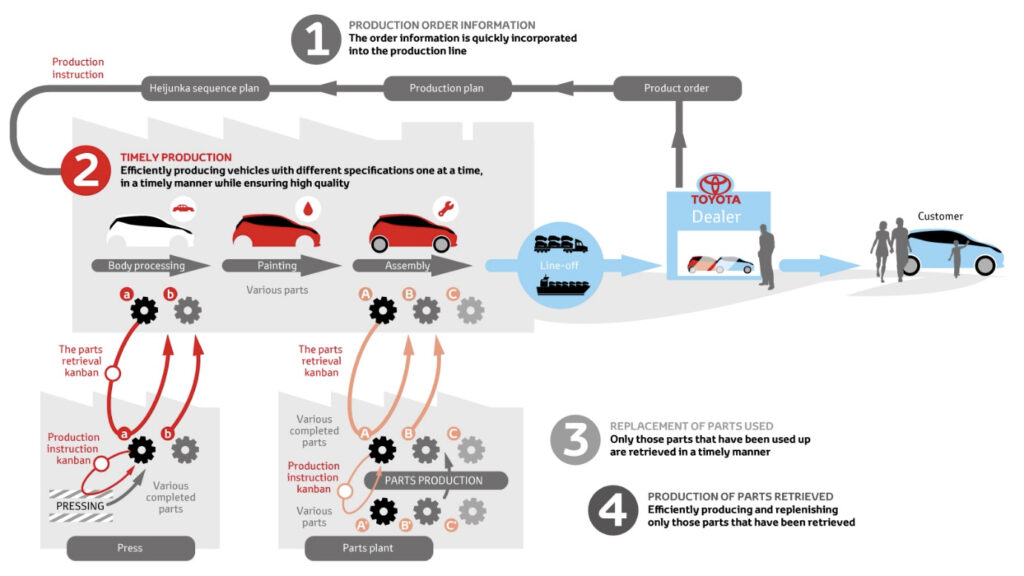

By ordering and stocking parts as needed, Toyoda reduced unnecessary inventory. When complemented with other strategies, the resultant savings enabled Toyota to overtake American automakers and rise to the top.

The lesson was clear: dispose of trash or don’t buy what you don’t need—order the bare necessities and put in place stringent quality controls. Then, increase your revenues by keeping upstream suppliers available to generate inventory on-demand.

JIT became the primary manufacturing method for a wide range of products, from automobiles to electronics to fast fashion.

However, JIT had a problem. Suppliers had to be faultless in delivering inventory or raw supplies on time, every time. So, if one supplier failed to meet a deadline, the entire production halted. Factories used to have months’ worth of components on hand accounting for this possibility but incurred greater expenses.

Enter COVID-19. The regular flow of parts crumbles under the weight of lockdowns, quarantines, sickness, and social isolation. While most regard the existing production method (JIT) as undeniably efficient, it suffers from ongoing reputational damage because of coronavirus.

Much agility in the supply chain was lost due to JIT’s brittleness and inability to shift gears when important suppliers came under pressure. Is JIT dead? No. The answer lies in innovation, and in embracing new technologies.

3D Printing in Manufacturing and Global Supply Chains

3D printing saves time, money, and helps preserve the environment.

It generates nearly no waste, minimizes overproduction, and lessens the environmental impact of the process overall (i.e., by requiring fewer inputs). 3D represents the next stage of JIT.

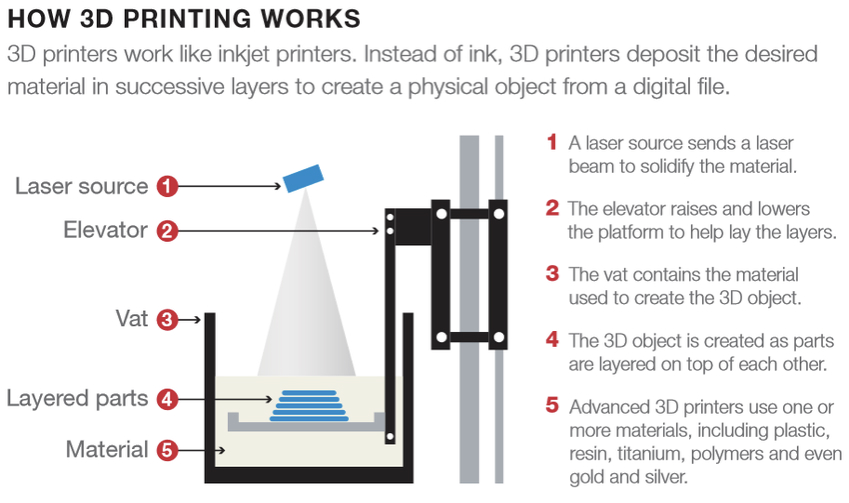

Even in the 1980s, researchers created 3D models using photo-hardening polymers or sheets of stacked powdered metal.

At the time milling and laser sintering were the primary material removal methods, rather than contrary additive techniques, so the process didn’t garner much attention at the time. Additive means to manufacture by adding sequential layers of material, as opposed to removing from a larger template or block.

It took until the turn of the millennium for 3D printing using liquid resins to become widely popular. This launched a new fascination with metalworking, resulting in shortened supply chains, lower production costs, and reduced waste.

The current supply chain disruptions should accelerate the adoption of 3D printing and robots as workforce shortages persist. 3D printing and robots may grow at a rate of 56% per year, from a public enterprise value of $70 billion in 2020 to over $6 trillion in 2030.

Understanding 3D Printing and Robotics

There are various ways that 3D printing can help to reinvent supply chains and strategies like JIT.

Decentralization

Because this technology is ‘portable,’ enterprises transport their products to local markets or clients faster. It’s likely we will see a sizable shift away from low-cost mass production towards local assembly hubs.

Low-cost mass production also suffers from hiking input costs in the event of trade wars or similar geopolitical tensions—further pushing the need for 3D printing.

Inventory and Logistics

Transporting physical items across countries and continents becomes less necessary as “on demand” production turns into the norm. With fewer stock-keeping units needed for production, the dynamics surrounding storage and tariffs change drastically. In effect, they feel unnecessary or obsolete.

Speed of Prototyping

Volkswagen is using 3D printers to produce tooling equipment at its factory in Portugal. Producing parts internally reduces production costs by 90% and cuts lead times to days rather than weeks.

For example, a liftgate badge once took 35 days to develop with traditional manufacturing, costing around 400 Euros. 3D printing produces the tool in four days at the cost of 10 Euros.

Product Customization

3D printing allows companies to create products tailored to their customer’s individual needs and improve the overall consumer experience.

This leads to flexible supply chains responding quickly to market developments. Design, manufacturing, and distribution might eventually integrate into a single supply chain function with higher customer engagement throughout the entire cycle.

Ownership and Control

Manufacturers of 3D printed items may create and distribute the goods directly, giving them total control over the materials used in manufacturing, storage, and distribution. Alternatively, and to fully profit from the benefits of 3D printing, they may offer digital files allowing the buyer to build the item themselves.

Because digital files are easily copied and shared, intellectual property and copyright infringement will likely be a deterrent for enterprises considering digital distribution. However, this strategy provides revenue continuity during times of heavy shipping backlogs, like with the ongoing pandemic.

Use Cases for 3D Printing

The potential uses for 3D printing span several industry verticals.

Healthcare

When COVID-19 triggered a scarcity of ventilators worldwide, many patients were forced to seek medical assistance. Several organizations and businesses responded with 3D-printable alternatives.

3D-printable splitters allowed multiple patients to share a single ventilator machine, whereas the ventilators and adaptors enable commercially available snorkelling masks to be adapted for ventilation purposes, all of which can be printed and assembled on-site.

In the same way, the need for nasal swabs spiked early in the pandemic, and multiple 3D printed choices are now publicly accessible for download and printing to meet that need.

Personal objects like face masks may be made more comfortable and well-fitting using 3D printing and other technologies, such as 3D laser scanning, which creates a digital model of the wearer’s face and enables computer-aided design manipulation. It’s also possible to melt down 3D printed objects to their constituent polymers and reuse them for future 3D printing projects, making them recyclable.

Construction

Even though the technology is still in its infancy, building giants have begun to appreciate the promise of 3D printers and have already made considerable advancements. The market for 3D printing concrete was approximately $56.4 million in 2021.

As a result, an increasing number of businesses are forming in this field to develop fresh, cutting-edge ideas. Russian 3D printing company Apis Cor is able to produce a complete house in under 24 hours.

Source: https://youtu.be/xktwDfasPGQ

Food

Soon, we may be able to prepare meals in our kitchens using 3D-printed ingredients. Innovative food products with unique shapes and recipes are being developed by a growing number of organizations incorporating 3D printing technology. A 3D printer for edible items has already been developed by Hershey’s and 3D Systems.

Chemicals

The chemical industry has an enormous chance to innovate and develop new income streams through 3D printing technology. As it collaborates with 3D printer manufacturers to produce new materials suitable for additive manufacturing, the industry is likely to be the new center of the production process.

Major chemical businesses are already collaborating directly with 3D printer manufacturers to develop new resins, polymers, and powdered metals to usher in a new era. BASF, a chemical powerhouse, is one of the corporations leading the way with a dedicated 3D printing branch. It’s already collaborating with many hardware OEMs, software providers, and materials specialists.

Summary

The pandemic has accelerated the additive manufacturing revolution, and businesses may need to act sooner than they might think. Organizations should start reviewing their supply chains to understand the opportunities of 3D printing and how the technology can improve efficiencies.

It’s clear that traditional methods are not working in a post-COVID-19 world, and that focusing on innovation ensures a lead ahead of the competition.

Disclaimer: The author of this text, Jean Chalopin, is a global business leader with a background encompassing banking, biotech, and entertainment. Mr. Chalopin is Chairman of Deltec International Group, www.deltecbank.com.

The co-author of this text, Robin Trehan, has a bachelor’s degree in economics, a master’s in international business and finance, and an MBA in electronic business. Mr. Trehan is a Senior VP at Deltec International Group, www.deltecbank.com

The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in this text are solely the views of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect those of Deltec International Group, its subsidiaries, and/or its employees.